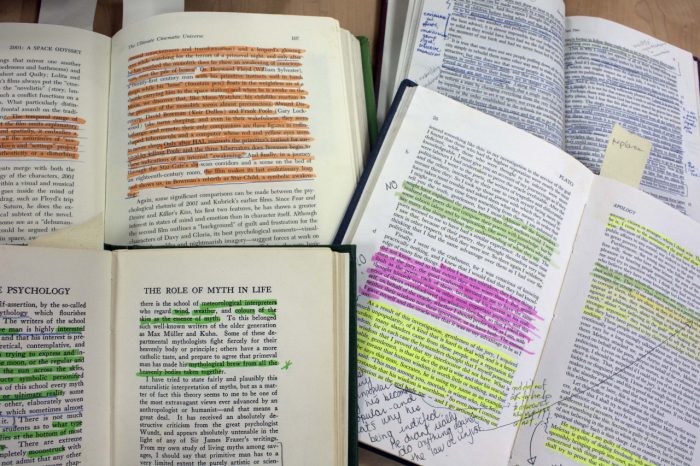

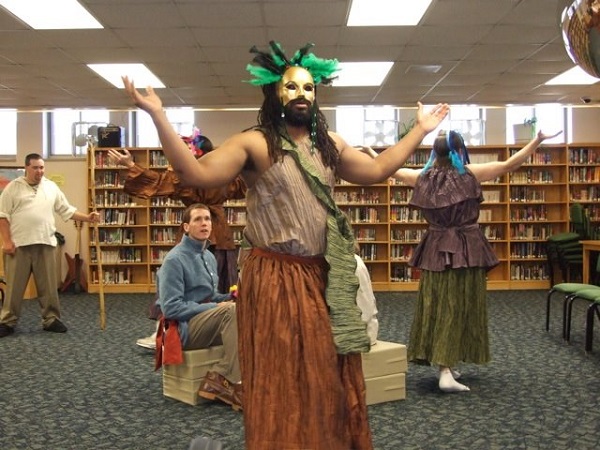

Three prison inmates walk onto a stage. No, it’s not the beginning of a bad joke. It’s a production of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, performed in California’s Solano prison and starring— among others— a former drug dealer, a convicted murderer, and a man who once beat someone nearly to death with a baseball bat. The performance is part of “Shakespeare for Social Justice,” an outreach program run by the Marin Shakespeare Company (MSC) as part of California’s Arts in Corrections program. In addition to their program at Solano, the MSC also has a Shakespeare program at San Quentin prison. Both programs consist of weekly classes, where inmates gather to read, discuss, and rehearse one of Shakespeare’s plays. They share personal stories, talk about the text, and play theater games. The program culminates in a fully staged production of the play, performed for both other inmates and members of the public.

Source: Marin Shakespeare Company

Arts programs in prisons are nothing new. Across the country, many prisons have programs meant to engage inmates in the arts, including theater, visual arts, and creative writing. Studies have shown art therapy to be extremely effective at improving an individual’s mood, socialization, and problem-solving skills. Accordingly, inmates who participate in arts programs subsequently have fewer disciplinary reports and lower rates of recidivism than those who do not. Shakespeare for Social Justice, however, is one of several programs that focus specifically on the works of Shakespeare as a tool to connect with— and possibly transform— incarcerated individuals. Similar programs include Shakespeare Behind Bars (SBB), which has programs for adult and juvenile inmates in Michigan and Kentucky; Shakespeare In The Courts, a program for juvenile offenders in Massachusetts; Shakespeare In Shackles, which operates in a maximum security facility in Indiana; and the Shakespeare Prison Project (SPP) in Wisconsin.

Source: CNN

The programs appear to be having the desired effect. From 2004-2008, the Racine Correctional Facility, home of the SPP, had an annual average of 1.92 disciplinary reports per inmate. During that same time period, however, participants in the SPP had an annual average of just 0.18 disciplinary reports per inmate— a rate ten times lower than that of the rest of the prison. In 2004, the year the SPP was introduced, the prison had roughly 2.25 disciplinary reports per inmate. During each year of the program’s existence, the rate of disciplinary reports dropped, ending at 1.54 reports per inmate in 2008, when the program was canceled. In the two years directly following the cancellation, the rate of disciplinary reports shot back up to 2.85 per inmate (data on disciplinary reports following the reinstatement of the SPP in 2014 are not available). Similar results come from the Shakespeare in Shackles program in Indiana. During and after their participation, the twenty inmates who spent the most time in the program had only two disciplinary writeups among them, and those were merely for cell phone possession. Prior to the program, those same twenty men had a total of over 600 writeups, many for violence. Participants in these programs fare better outside of prison, as well. The average rate of recidivism nationwide is 60%. In Kentucky, one of the states where SBB operates, the recidivism rate is 29.5%. The SBB program, meanwhile, has a recidivism rate of just 5.1%.

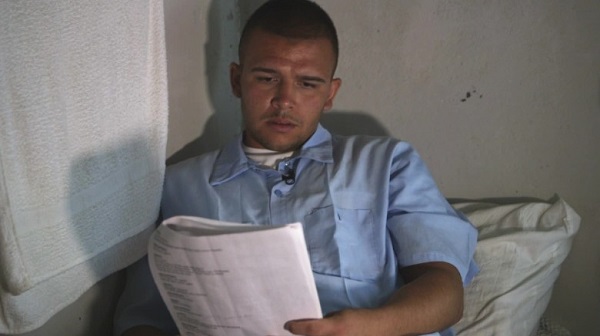

Personal anecdotes back up the numbers. “I saw guys change,” Ronin Holmes, a California inmate, says of the MSC program. “I watched men change from these quiet, hardened individuals, to these open, happy, laughing men.” Rex Hammond, a career criminal and participant in the Shakespeare in Shackles program, says that reading the plays “started opening my mind, getting me to think outside myself.” According to Lesley Currier, who runs the MSC program at Solano, “of all the men who have been our students and gone out into the world, there’s only one we know of who has returned to prison.” Many supporters of these programs believe that their success is due not just to the education and sense of community they provide, but to the power of Shakespeare to connect with marginalized and disenfranchised populations. This is certainly the view of Laura Bates, the founder and director of Shakespeare in Shackles. A key part of the program for her is encouraging inmates to think critically about the text and apply it to their own lives. “Shakespeare has the power to educate convicted killers and help them examine the choices they made that landed them here—and how to avoid making those choices again,” she says.

Source: National Geographic

For many inmates, engaging with Shakespeare helps them come to grips with painful incidents from their own past. Such is the case for Steve Miller, a Wisconsin inmate who played Cordelia in an SPP production of King Lear. Lear’s abandonment of his daughter reminds Miller of his own mother, who once told him she should have aborted him. Taking on the role of Cordelia gave Miller a place to finally vent his pent-up feelings of anger and sadness toward his dysfunctional family. Shedding tears onstage when Cordelia is reunited with her father marks the first time Miller has ever cried in front of other people. “I can use putting on the costume as an excuse to show emotion,” he says. “This lets me vent out my frustration. It lets me vent out my sadness. I’ve never actually done that.”

Source: Shakespeare Prison Project

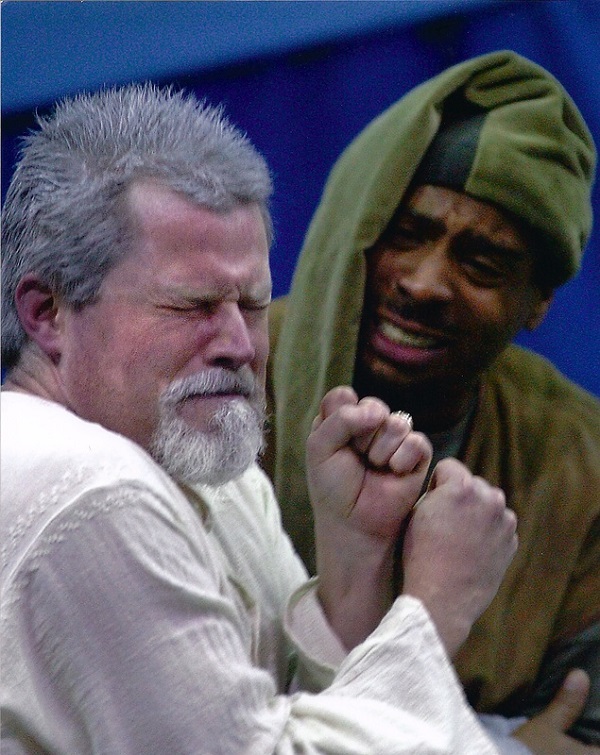

Some inmates continue their relationship with Shakespeare even after their release. Dameion Brown, who participated in the MSC program at Solano, is one such example. After serving twenty-three years in prison, Brown now works in professional theater. A year after his parole, he landed the title role in an MSC main stage production of Othello. “Shakespeare in prison was the point where I started to believe that a better breed of people cared about the existence of those of us incarcerated,” he says. In addition to acting, Brown also counsels young men, to help keep them out of trouble.

Source: Shakespeare Prison Program

Even inmates who are not released find new beginnings with the Bard. Larry Newton, an Indiana inmate, is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole at a maximum security facility. Prior to his participation in the Shakespeare in Shackles program, he was frequently violent, had attempted excape several times, and had been in solitary confinement for ten years. Following the program, Newton was released from solitary and has gone on to write manuals and workbooks designed to help other inmates read Shakespeare. His interpretations have even been cited in scholarly papers and at conferences. “Shakespeare saved my life,” he says.

Stories like Newton’s and Brown’s don’t surprise Currier. “What [these stories] prove,” she says, “is that some of the people who we incarcerate have a lot to give back to the world, if only we would let them.”

YouTube Channel: Shakespeare Behind Bars

Featured image via Marin Shakespeare Company