“It is not the office of art to spotlight alternatives, but to resist by its form alone the course of the world, which permanently puts a pistol to men’s heads.” (Theodor W. Adorno)

Long have artists – whether they be literally artists, or musicians, or writers – found themselves entangled in politics and through their craft fought back against the oppression that threatened them. The twentieth century, in particular, saw many artists the world over necessarily stand up to tyranny through their work and, unfortunately, that has had to continue in the twenty-first century, too.

On this subject, Hyperallergic recently compiled a list of 5 books that give a broad view of artists’ different responses to the Nazi regime, from its beginning to its end; how they survived and coped during that horrific time. It is a wide moral spectrum, to say the least.

1. George Grosz: Art and Politics in the Weimar Republic by Beth Irwin Lewis

Grosz was famed for his satiric depictions of “plutocrats, militarists, industrialists, and war profiteers,” which illustrate the artist’s rage against “oppression and stupidity” just before the Nazi regime, in the Weimar Republic. Interestingly, following on from the Dada movement of WWI, Grosz’s work was so perceptive that even today his portrayal of the evil he experienced, the “sickness of the society around him,” seems familiar. Having riled the incoming Nazi party, the artist finally fled to America only “a few days before Hitler came to power.”

Source: Amazon

2. An Artist against the Third Reich: Ernst Barlach, 1933-1938 by Peter Paret

Ernst Barlach, “one of the most important sculptors of the twentieth century,” refused to remain silent when Hitler had his work destroyed in a bid to “rid Germany of ‘international modernism’.” Instead, during the early years of the Third Reich, Barlach continued to create – no mean feat when there was a ban on “exhibiting, teaching, and even making work” – but some among the national socialists believed in a Nordic Modernism to “serve” their purposes, so he stayed afloat for a short while. Yet, by the late 1920’s his career was over and the period from 1933-1938 (the year of the sculptor’s death), which Paret here covers, details Barlach’s desperate epistolary protests against his ill treatment.

Source: Amazon

3. Mephisto by Klaus Mann

In contrast to Barlach and Grosz, Mann used his experience of oppression to write Mephisto, a roman à clef focused on presenting an artist who saw life under the Nazis as a time of opportunity. Mann’s protagonist is actor Hendrik Hofgen, based none too vaguely on Gustaf Gründgens, “an ex-Communist who joined the Nazis to become the director of Germany’s state theater during the Third Reich,” and who abandoned both his wife and mistress to do so. Comparable to Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (not especially subtly, Hofgen’s ticket to fame come from playing Mephistopheles – i.e. Mephisto – in Goethe’s Faust), the book was written while Mann was in exile.

Source: Amazon

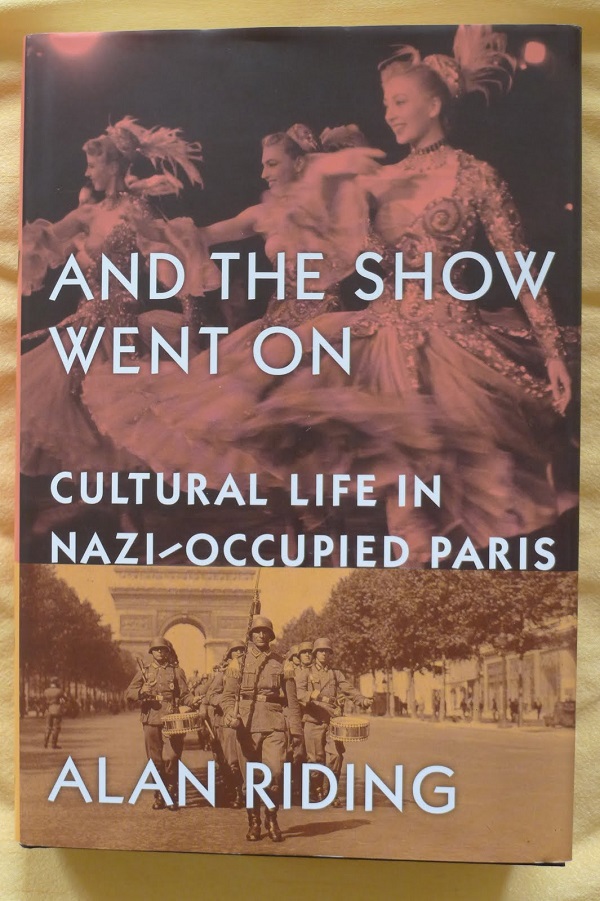

4. And the Show Went On: Cultural Life in Nazi-Occupied Paris by Alan Riding

After the Nazis occupied France in 1940, their treatment of artists therein was somewhat different to the state of things in Germany. Though the Jewish and communists were still “purged,” art galleries and theaters continued with business as usual, books were still published, and generally creative freedom was permitted – so long as there was no discernible criticism of the occupation. Riding’s book explores the “moral duty” artists have, or otherwise don’t, in regards to their behavior in such circumstances. Fascinating.

Source: Amazon

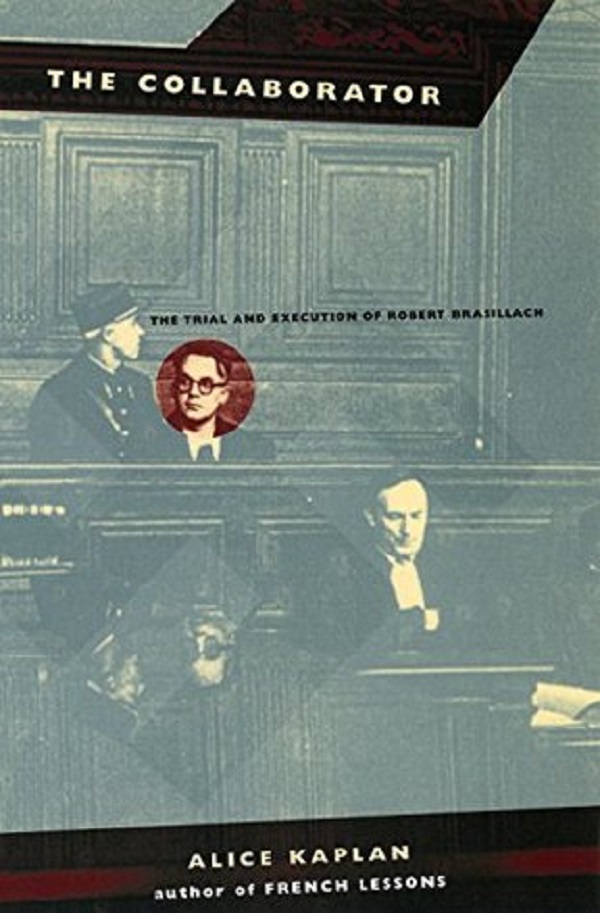

5. The Collaborator: The Trial and Execution of Robert Brasillach by Alice Kaplan

On the other side of the coin, The Collaborator presents a tale of justice. Brasillach was a novelist and literary critic who was executed for treason by a French firing squad in 1945. Editor-in-chief on a fascist publication, he was outspokenly anti-Semitic and denounced resistance fighters. Kaplan expertly explores all sides of this history of retribution, asking why Brasillach in particular was made an example of for his detestable behavior under the Nazi regime.

Source: Amazon

As Anthony Papa said, “Art can be a weapon of the oppressed.” This, all know.

YouTube Channel: CBS Sunday Morning

Featured image via Art Observed

h/t Hyperallergic