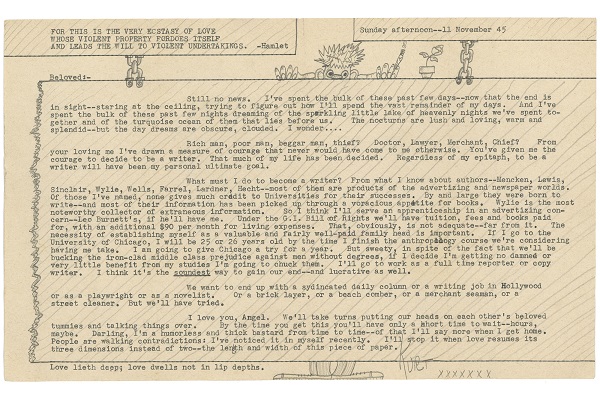

“Rich man, poor man, beggar man, thief; Doctor, Lawyer, Merchant, Chief.”

So wrote Kurt Vonnegut to his new wife, Jane (née Cox), in the autumn of 1945. Twenty-two years old, awaiting discharge from the Army, and riddled with doubt about his future career, Vonnegut wrote to Jane often, as Ginger Strand writes in the New Yorker.

Source: New Yorker

The “first eleven letters are at Indiana University’s Lilly Library,” but the Vonnegut family has many, many more within their possession. It is a collection started by Jane herself – but only of Kurt’s letters, not hers. This, however, does not necessarily relegate her to the shared dark history many women endured in the past. For Mrs Vonnegut had an agenda; she knew precisely which career was “written” in the stars for her husband: that of a writer.

“[The letters’] passionate and thoughtful character instructs us […] to re-see what we may have missed – to write Jane Back into the story and acknowledge the clear-eyed ways in which she helped shape the Vonnegut narrative, both in life and on the page.”

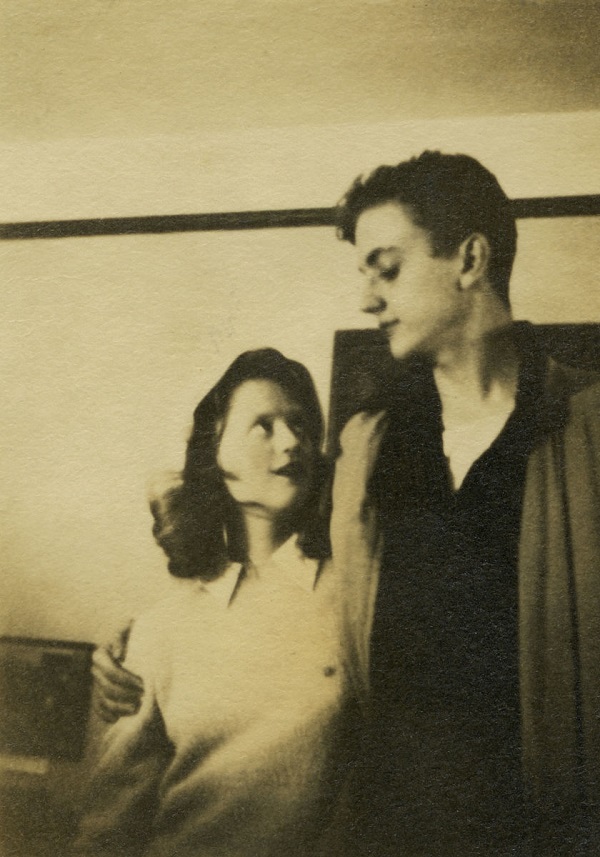

Having known each other since kindergarten, the Vonneguts’ relationship developed over time through friendship, before anything more – a bond continued by their letter-writing. But, as Strand writes, Kurt always knew he would wed Jane.

“[H]is main subject was their mutual future […] They would have a home with books and art and a well-stocked bar. They would have friends over for intellectual conversations. They would have seven kids. He traced sevens behind his paragraphs and signed most of his letters with seven X’s.”

Source: 5 Harfliler

This creative illustration of his letters was a frequent thing. Often, he drew “yin-yang symbols,” too, to show that “they were two halves of a single whole” (inspiration, it seems, for Howard and Helga Campbell in Vonnegut’s Mother Night).

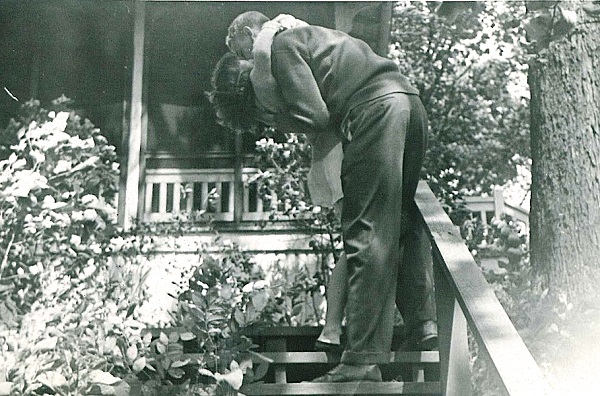

Writing, in fact, was in both their sights and in the beginning Kurt demurred to what he saw as the greater talent in Jane. Indeed, he contemplated many professions, “teaching, reporting, opening a library with a bar.” Jane, however, would have none of it and insisted he read Russian classics (The Brothers Karamazov was their shared favorite) and write stories, while he awaited discharge from the Army. Kurt obeyed, sending her the drafts with his letters, so that she could edit them.

“Angel, please go over the crap I’ve written for spelling and punctuation. I can picture you reading along and suddenly looking pained; running to get a pencil to hide from the world the astonishing gaps in the education of your loving husband.”

Source: New Yorker

Self-belief came by November of 1945, though. Having been reading Newsweek, he realized that the reporting on “foreign affairs” seemed ancient history, as he himself had been there while serving in the Army. This moment of clarity was the spark for the thought seed of Slaughterhouse Five; the strength to write of his “war experience,” however, he still claimed he owed all to Jane.

“From your loving me I’ve drawn a measure of courage that never would have come to me otherwise. You’ve given me the courage to decide to be a writer.”

This confidence would be given for the next twenty-five years. Certainly, without the couple’s many conversations and philosophizing, ideas such as Vonnegut’s fictitious religion, Bokononism (as seen in Cat’s Cradle), would perhaps not exist.

Nevertheless, the more successful Kurt became, the more the two drifted apart. By 1969, the year Slaughterhouse Five was published, their marriage was over.

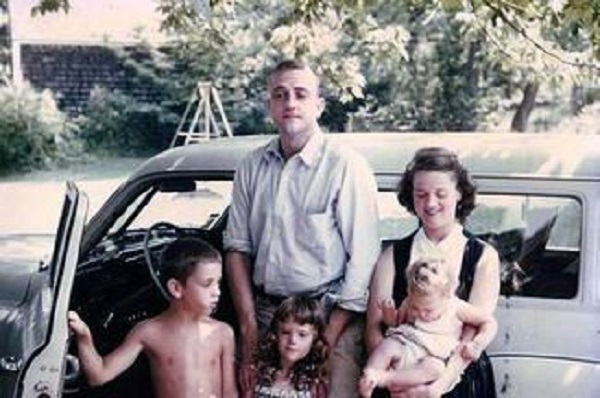

Strangely, in 1958 the double tragedy of the death of Kurt’s sister, Alice, and her husband within days of each other meant that Jane and he adopted their four children. As Strand writes, “Added to their own three children, that made the seven Kurt always said they would have.”

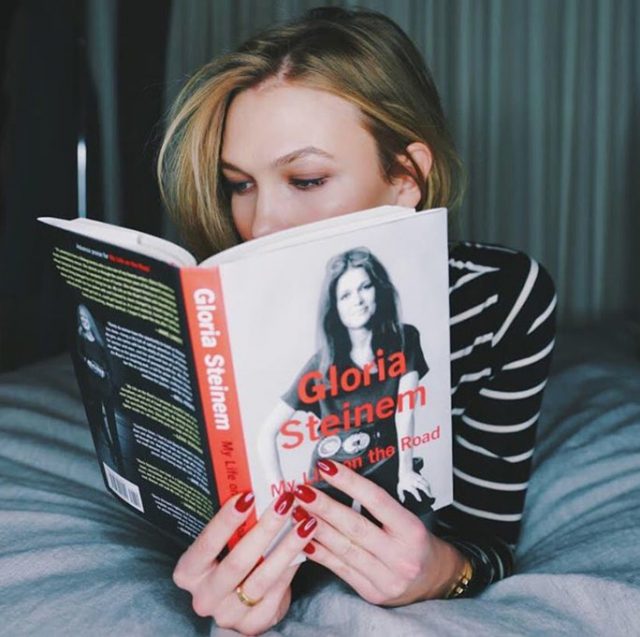

Source: Wikipedia

When Breakfast of Champions came out in 1973, Vonnegut received mixed reviews. Kurt next wrote the 1976 Slapstick, a semi-autobiographical novel with an autobiographical preface, wherein he declared that “his own sister Alice was the person he had always written for.” Though he thus publicly claimed his sister as “the secret of my technique,” Jane was in his mind as well, as he had once proclaimed in 1943:

“[Y]ou are the one person in this world to whom I like to write. If ever I do write anything of length – good or bad – it will be written with you in mind.”

On this evidence, Strand suggests a new reading of Slapstick: that of Jane as Eliza Swain, instead of Alice:

“Read as a valedictory rumination on the end of a marriage, on the loss that attends the collapse of any nation of two, “Slapstick” is a much better novel.”

Source: Prabook

Jane went on to remarry, became Jane Vonnegut Yarmolinsky, but she still phoned Kurt when terminally ill with cancer and requested that he “tell her what would determine the moment of her death.” Vonnegut considered that “she may have felt like a character in a book by me.” Seemingly emotionless words, but for a couple who had been a single entity for so long a period (and for the purpose of such a goal as Kurt’s writing career), Strand concludes that:

“Jane Vonnegut was in some sense a character invented by Kurt. But only in the sense that Kurt Vonnegut was, and equally, a character invented by Jane.”

The Vonneguts truly became the yins and yangs that adorned so many of Kurt’s letters. Theirs was a life lived for writing and closed with writing of a life so lived.

YouTube Channel: svsugvcarter

Featured image via New York City Center

h/t New Yorker