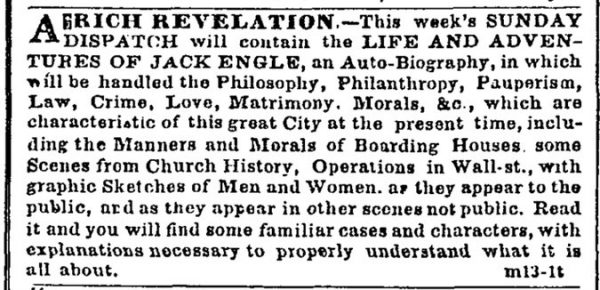

On March 13, 1852, The New York Times published a small advertisement on Page 3 for an anonymously written serial tale that would begin the next day in a rival newspaper.

“A rich revelation,” the advertisement began, promising a rollicking story that would touch on “the Manners and Morals of Boarding Houses, some Scenes from Church History, Operations in Wall-st.,” and “graphic Sketches of Men and Women.” This story, however, did not meet with great success: it was neither reviewed nor reprinted, and was soon forgotten by the literary minds of the day.

Source: New York Times

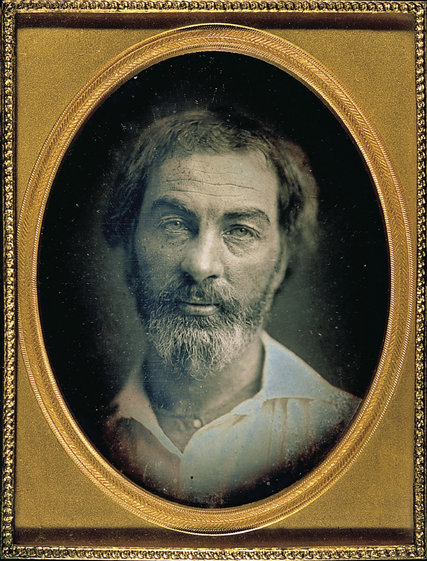

Today, however, scholars and critics are practically dancing up and down in glee, for it turns out that the “anonymous” writer behind this 36,000-word tale was in fact Walt Whitman, the famously radical poet behind Leaves of Grass.

This story, titled Life and Adventures of Jack Engle, represents Whitman’s take on the city mystery novel, a popular genre of his time that pitted members of the 1 percent against the lower classes. A quasi-Dickensian tale of an orphan’s adventures, Jack Engle features a villainous lawyer, virtuous Quakers, glad-handing politicians, a sultry Spanish dancer, and more than a few unlikely plot twists and jarring narrative shifts.

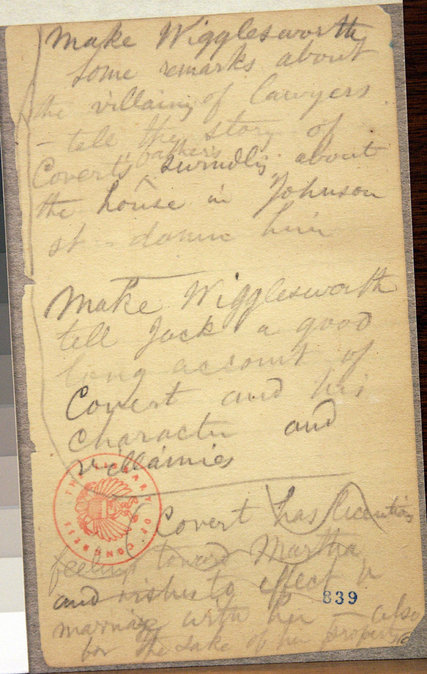

Zachary Turpin, the graduate student at the University of Houston who discovered this lost work last summer, dubbed it “rollicking, interesting, beautiful, beautiful and bizarre.”

Source: New York Times

But scholars appreciate Jack Engle as more than just an interesting work in and of itself: the majority of their interest stems from the fact that Jack Engle provides a window into both Whitman’s creative process and his transformation from workaday journalist to sensuous, philosophical poet.

“It’s like seeing the workshop of a great writer,” said Ed Folsom, the editor of The Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. “We’re discovering the process of Whitman’s own discovery.”

David Reynolds, a Whitman expert at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, says that Jack Engle and the other “raffish” young male characters are reminiscent of the man-of-the-streets persona Whitman creates for himself in Leaves of Grass: “Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs.”

Source: New York Times

Moreover, in Chapter 19 of Jack Engle, the narrator enters the cemetery at Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan and wanders among the bodies of fallen men like Alexander Hamilton and Captain James Lawrence.

“Long, rank grass covered my face,” says Jack, the first-person narrator. “Over me was the verdure, touched with brown, of trees nourished from the decay of the bodies of men.”

In this chapter, Whitman sacrifices progression in the plot for the opportunity to indulge in reveries on nature, immortality, and oneness of being that strikingly echo the imagery in Leaves of Grass. Mr. Turpin also says that Chapter 19 reminds him of “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” one of the most famous poems in Leaves of Grass, wherein Whitman declares, “I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence.”

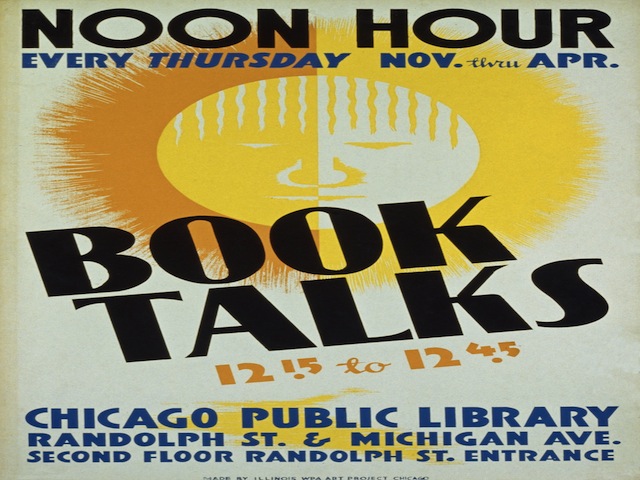

Source: La Cronica Badajoz

Ironically, the poet himself would likely be rather less than delighted that this early work has been rediscovered. “My serious wish,” Whitman wrote in 1882, “were to have all those crude and boyish pieces quietly dropp’d in oblivion.” In 1891, when a critic planned to republish some of his early tales, he was amusingly blunt: “I should almost be tempted to shoot him if I had an opportunity.”

Many apologies, Whitman, but we’ll just have to bear your enmity as best we can. As Whitman himself said, “Nothing is ever really lost, or can be lost.”

YouTube Channel: SpokenVerse

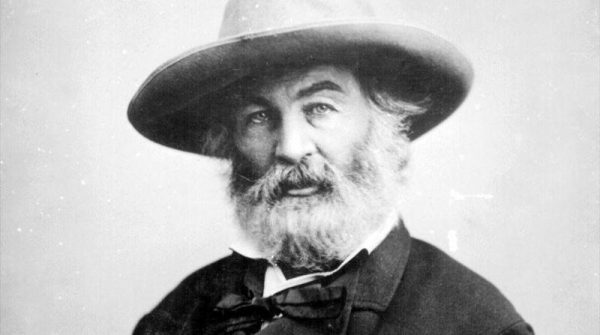

Featured image via Cleveland Poetics