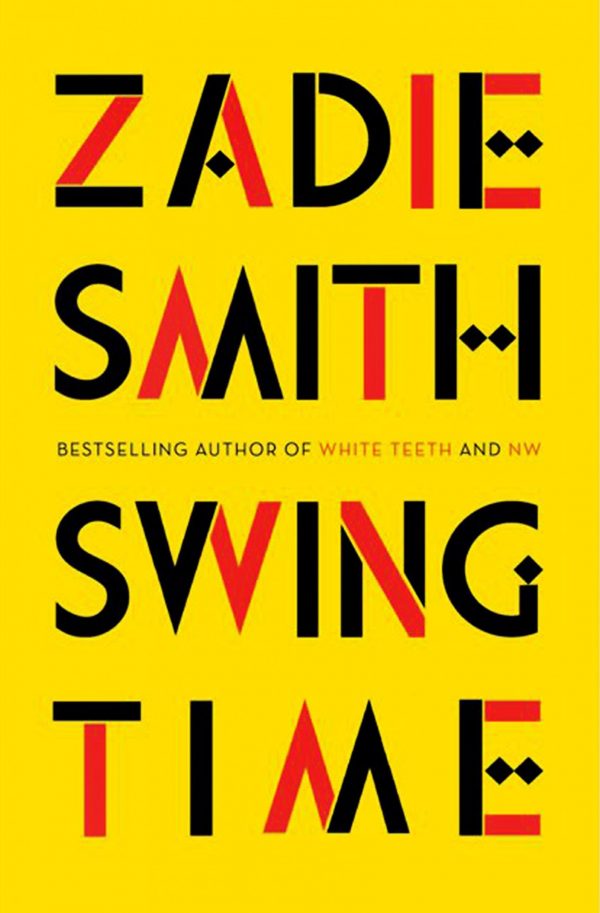

Zadie Smith, at only 41 years old, is already a name many of us recognize. She hit the ground running with the publication of her first novel, White Teeth, in 2000, and has continued to release nothing but genius since then. Her new novel, Swing Time, published this month, not only holds this standard, but transcends it.

Source: Pixabay

Learning more about Mrs. Smith, I realized how autobiographical this novel was. Zadie, like her main character, grew up in England the child of a white father and Jamaican mother, took dance lessons, and developed ambitions to be a dancer. However, Mrs. Smith went on to find her passion in writing.

Source: Shadow And Act

Swing Time is a mammoth achievement of artistry and honesty. The story of a person’s life spanning 30 years, Swing Time is brutal, beautiful, simple, global, and reflective.

Told in first person, the main character in Swing Time is never named. She stands for all of us as we come of age, change our minds, experiment, shy away from confrontation and opportunity alike, and try to come to terms with our place in the world. The structure of the story is complex, but never confusing. The book starts off in the narrator’s adulthood, at a turning point. Then we back up to her childhood. With chapters oscillating between adulthood and childhood, we work our way inwards from the bookends of her life until they converge. In this way, time itself becomes a key character in this story.

Source: Amazon

Swing Time was originally a Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movie from 1936. As a child, the narrator and her friend Tracey are obsessed with dance: they both study ballet and tap at a local, Saturday class, and have aspirations of becoming dancers. At a young age, these mixed-race girls are acutely aware of class, race, and gender, and what those mean in terms of someone’s educational and career opportunities.

The narrator has a childhood friend named Lily Bingham who solemnly proclaims that she is “color blind,” meaning, she just doesn’t even see different races: we’re all the same. At her core, I think that this is how the narrator is as well. She looks at her world and sees art, beauty, quality, or the lack thereof, despite class, race, or gender. The first chapter in the book has a passage in which the narrator is showing a clip of Swing Time to a black friend, because she loves the dance so much. But as her friend frowns while watching it, she realizes, “I hardly understood what we were looking at: Fred Astaire in black face” (Smith 4). Throughout the entire book, there is constant dialogue from her Jamaican mother, Tracey, college boyfriend, three different employers (covering the lower class, middle class, and extreme upper class), and even the narrator herself about “tribe.” “Our people” is a common phrase, one that the narrator fixates upon at one point, trying to resolve. As an adult, she meets another version of Lily Bingham in the form of a world-famous pop star, Aimee. It’s not that Aimee doesn’t see color, class, or gender: it’s just that since she was able to transcend many of these barriers herself (rising up out of the Australian wilderness to fame), so she has difficulty seeing why anyone else would be limited by their birth and surroundings.

Source: Pixabay

And thus, we are presented with the most key and crucial questions a coming-of-age story introduces: who am I and what is my place in this world? The narrator wants it to be simple: “I’m just a person, my place is obvious.” She comes to find that she is unaware of her passions, her style, and her talents. She lets the world around her shape her, adopting methodologies of those nearest her, while also rejecting any kind of control anyone seems to be initiating in her life. Her mother, an autodidact, and her adulthood employer, Aimee, a world-famous singer, both pulled themselves up in this world by their bootstraps, running on nothing but their conviction. Hollow and cynical, the narrator rejects this, as she sees everyone else in her life conform to the box they were born in: her mother and Aimee are the exception, not the rule. The narrator never really considers that she too could be an exception.

Source: Pixabay

Maybe what the reader comes to realize is that, though our histories shape the world we live in, and–to some extent–the world we will always carry with us, our passions shape our lives. The first step to transcending the restraints we were born with is finding something bigger than those to believe in–something we can’t live without–and investing in that with everything we have. For some people, that’s music; for some, it’s advocacy; for some, it’s family; and for others, it’s dance. We are constructed from our history, both immediate and spanning the globe and many centuries. Aimee believes in fate: that her future is just as sure as her past. How do we reconcile our vast pasts with our dreams for our future? How do we make them work in tandem to create, not a life that is expected of us, but a life that we desire?

Book Suggestions:

- Commonwealth by Ann Patchett

- Nutshell by Ian McEwan

- Today Will Be Different by Maria Semple

YouTube Channel: Rosiana Halse Rojas

Featured image via Bustle