Translator Mui Poopoksakul was recently asked by Words without Borders to write a discursive piece for a special November issue on the state of Thai writing within global publishing.

Poopoksakul’s response was hopeful, but hesitant. Her own, first full-length book translation (of a collection of short stories by Prabda Yoon, entitled The Sad Part Was) will be published by Tilted Axis Press next year. However, generally, very little Thai literature has been translated.

Source: Words without Borders

“We are a country of around sixty-seven million people, and Thai is the twenty-fifth most spoken native language in the world; the numbers should suggest a better outcome.”

Poopoksakul wonders whether it is because of Thailand’s appeal as “a good-time country,” a place where – as the Thai saying goes – there is “fish in the water and rice in the fields;” or whether readers believe the literature doesn’t offer deep enough a written meditation, given lack of enough perceived suffering.

Source: Pexels

Nevertheless, discussing the topic with the very Thai writers she translates, Poopoksakul uncovered a widespread vulnerability underlying their native literature:

“[Y]ou will find expressions of the disquiet of living in contemporary Thailand, a Southeast Asian nation where the rate of modernization seems only to accelerate.”

Geographically close to Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Malaysia, Thailand was recently bereaved of its ninth king in the Chakri Dynasty in October, King Bhumibol Adulyadej (or King Rama IX). It was the Chakri Dynasty that moved the country’s capital to Bangkok in 1782 and for the past seventy years King Bhumibol was head of its constitutional monarchy (changed from absolutist in 1932). Thailand has not been without political turbulence, of course, and has been under the latest period of military rule since 2014.

Source: Al Jazeera

Thus it is, Poopoksakul states, that Thai writers have evolved to be “a socially concerned and politically engaged bunch”, as discussed in her interview with editor Suchart Sawasdsri:

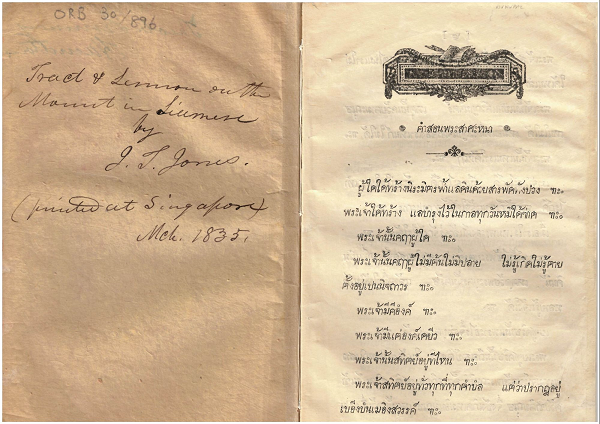

“Thai literature has had a long tradition of delivering social critique and promoting activism, going all the way back to the beginning of Thai prose writing about 140 years ago.”

Source: British Library Blogs

Indeed, Thai writing is quite a young literature (in the modern sense), with an “early” author, Kulap Saipradit, thought to have coined the Thai word for “novel” only in the 1920’s. Saipradit was stylistically “prototypical,” as well, with an intellectual and journalistic background that inspired his fictional penmanship.

There has been enough time to development “movements,” however, such as the “literature for life” movement (Thailand’s equivalent of social realism) in the second half of the twentieth century. Since then, modernist narratives have replaced realist and “leftist ideology” has been tweaked for the modern age. What has remained relatively unchanged is the existence of the “binary” in Thailand’s prose:

“[T]he urban and the rural, the divide between the capitalist life in the metropolis of Bangkok […] and the traditional life, often imagined as idyllic, in the provinces.”

Source: Petra Travels

In these contrasts, Poopoksakul sees evidence of the “growing pains of an evolving society,” as relevant to a still-developing nation concerned with “class, equality, tradition, democracy, and abuse of power.”

In addition to Poopoksakul’s exploration of Thai literature on the global stage and her interview with Suchart Sawasdrsi, the Words without Borders’ special November issue also features fiction from Duanwad Pimwana (blending social realism with magic realism to capture the essence of small-town Thailand), poetry from Phu Kradat (who, writing in his native dialect, is said to be “the new voice of the northeastern region of Isan,” fighting against the belief that his people are fated always to “become migrant workers”), and fiction by Sri Daoruang (deemed a heroine for rising from a factory job with only a fourth-grade education to become one of the most established voices in Thai literature as a whole).

Alongside these pieces, there is work by Win Lyovarin (“experimenting with narrative forms”), Chart Korbjitti (a “household name” in Thailand), Uthis Haemamool (challenging “the concepts and facts of history”), and writing by Pradba Yoon (whose work Poopoksakul translated for her forthcoming publication, The Sad Part Was, in 2017). In fact, all the writing cited has been translated by either Poopoksakul herself or Peter Montalbano in Words without Borders’ special November issue.

Source: Prezi

“I hope that the works presented here will begin a longer conversation about writing from Thailand. I myself will be watching what is to come from our authors now that the King’s death has plunged our country into a new era.”

Indeed, hopefully there will be much more translated Thai literature made available in the near future.

YouTube Channel: BBC News

Featured image via Tour Asia