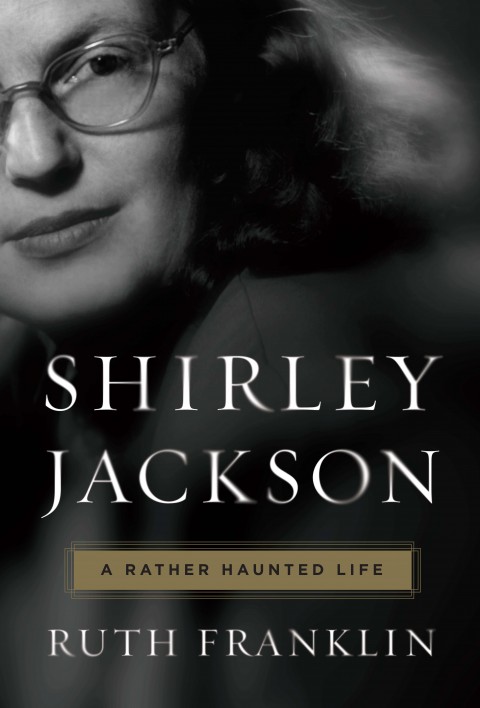

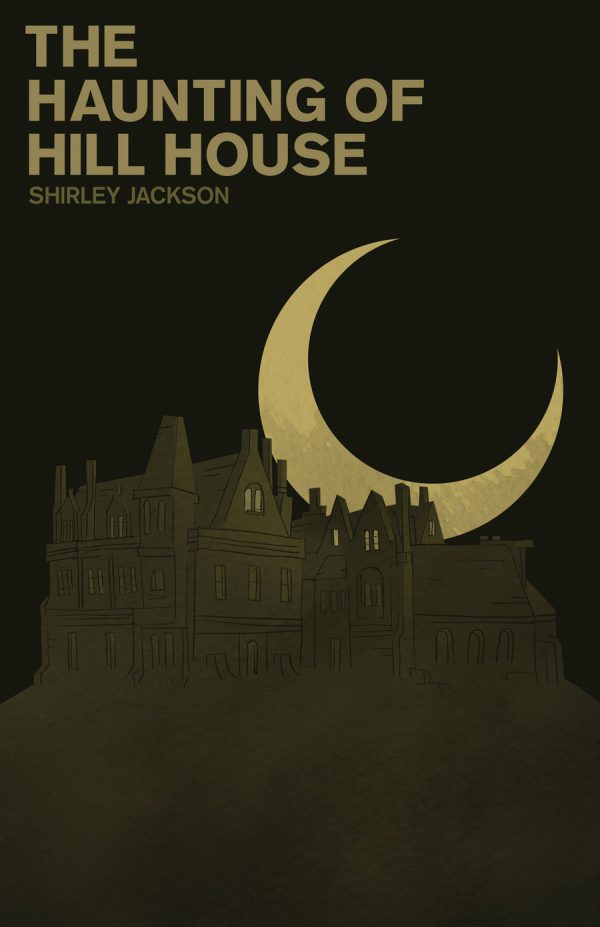

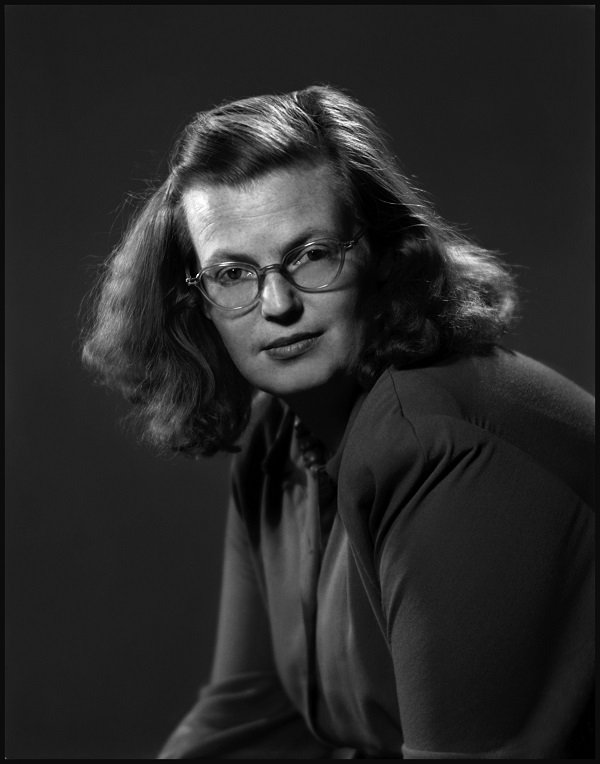

A new biography of Shirley Jackson, author of beloved ghost story The Haunting of Hill House, seeks to dismiss the standard relegation of the writer to middlebrow spookiness and instead reveal her longstanding proto-feminist intentions.

Biographer and book critic Ruth Franklin’s recently released A Rather Haunted Life asks of its readers that previous conceptions of the “Virginia Werewoolf” of horror, as Jackson was once dubbed, be set aside and the author’s behavior and creative output be reassessed. For, as Zoë Heller recently wrote in The New Yorker, Jackson was in fact “a major figure in the American Gothic tradition and a significant, proto-feminist chronicler of mid-twentieth-century women’s lives.”

Source: Amazon

A Rather Haunted Life contrasts greatly with Judy Oppenheimer’s 1988 biography, Private Demons, wherein the occult veneer of Jackson’s life was further pushed, the author having described herself publicly as “a practicing amateur witch” and boasted about the hexes she had made (all, Franklin argues, to tease; all to sell books).

Born in San Francisco in 1916, Shirley Jackson considered herself both an outsider and a writer early on in life.

“When I [sic.] first used to write stories and hide them away in my desk, i used to think that no one had ever been so lonely as I was and I used to write about people all alone […] I thought I was insane and I would write about how the only sane people are the ones who are condemned as mad and how the whole world is cruel and foolish and afraid of people who are different.”

Source: Amazon

This withdrawal into herself was influenced in no small part by her (quite awful) mother, Geraldine – a relationship which Franklin generously draws upon in her biography. A vapid woman disappointed in Jackson’s lack of interest in “feminine charm,” even when the author had left home Geraldine would send letters reiterating her distaste with both Jackson’s appearance and way of life. As Heller wrote in The New Yorker:

“Jackson’s adult life was ostensibly a rebellion against her mother and her mother’s values. She became a writer; she grew fat; she married a Jewish intellectual, Stanley Edgar Hyman, and ran a bohemian household in which she dyed the mashed potatoes green when she felt like it.”

Jackson’s marriage came about rather romantically, one could say, Hyman deciding she was the girl for him after reading her first published story Janice in a Syracuse University magazine. There, the romantic veneer per se ends. Unfortunately, the anxiety and depression that would haunt her throughout her life had already begun when they started dating, causing the early experiences of and reactions to Hyman’s promiscuity (and recounting of such to Jackson) to appear so anguished that he thought her mentally ill.

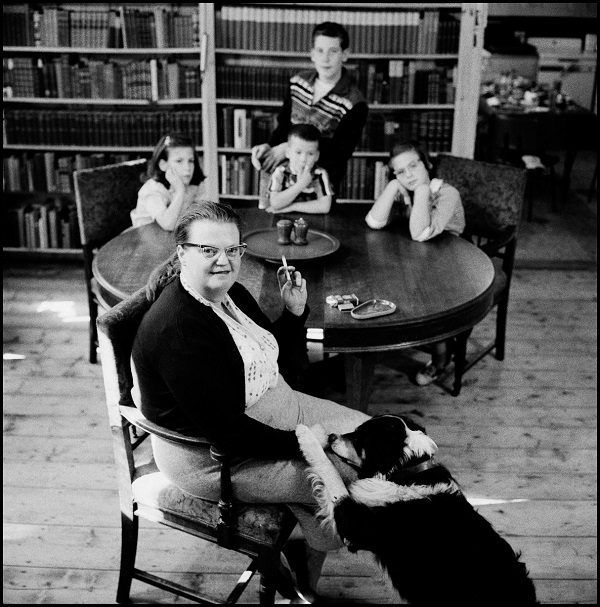

Marrying shortly after graduation, they moved to New York where they both worked as writers, Jackson for The New Yorker and Hyman for The Talk of the Town. Upon the birth of their first child in 1945, the couple moved to Vermont, where Hyman took up a position in the literature faculty of Bennington College. Three more children followed. Jackson fell sharply into the role of housewife, the busy domestic situation prompting her to write comic essays which she submitted to women’s magazines, describing a hectic life as wife and mother.

The truth, however, was much darker, the author having come to rely heavily on alcohol, tranquilizers, and amphetamines. Indeed, Jackson felt stifled, stuffed into the role of faculty wife, oppressed by her husband, and shunned by the North Bennington locals (an icy relationship that inspired her to use them as the model for the barbaric villagers in her 1948 story, The Lottery).

However, it was Hyman who could be considered the catalyst for the content of Jackson’s writing, his attitudes to marriage archaic even for then. Although Jackson became the higher earner, it was Hyman who held the purse strings (even though he belittled her writing to mutual friends; even though he continued his infidelity). So it is that Jackson’s tales feature the motif of “lost” women, lonely female figures attempting to escape claustrophobic environments, whether familial or locative. What then appear to be found sanctuaries are slowly unveiled as places of hidden evil, or lovers revealed as demonic.

Source: Amazon

In short, there is no real hope. Likewise, Jackson’s escape from under her mother’s roof was no escape at all, having found herself in the prison of her husband’s home.

The resultant rage she felt was largely contained within, but leaked into her prose (and “revenge-fantasy cartoons”). To the outside world, Jackson seemed a powerful woman of wit, who became aggressive if her writing was interrupted. Yet, fear was Jackson’s only hindrance in her life, the only reason she couldn’t leave Hyman. It was a fact she came to realize later on.

This dichotomy of personality features in her stories. The (female) protagonist is always unhappy, timid, restricted by a “demon of the mind.” This figure Jackson then contrasts with an alternative character, full of boldness, and blessed with a freedom the former can never hope to have. Ruth Franklin interpreted this as anticipatory of Betty Friedan’ 1950’s housewife description: the “virtual schizophrenic,” pressured to “deny her personal and intellectual interests and subsume her identity into her husband’s.”

Source: Bookforum

Heller, however, looked to Jackson’s writing (rather than her life), seeking therein Franklin’s biographical focus on Jackson’s “nascent feminist sentiment,” and came to a different conclusion:

“[W]hat keeps women inside these ghastly places is not societal pressure, or a patriarchal jailer, but the demon in their own minds. In this sense, Jackson’s work is less an anticipation of second-wave feminism than a conversation with her female forebears in the gothic tradition.”

Thus, to focus too much on the feminist element of Jackson’s work is to strangle the “haunted air” she injected into her prose. So, too, to ignore Jackson’s dark humor. Her final tale, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, finally saw her protagonist(s) attain a “fairytale ending”: this, by killing off family and barricading the house against intruders.

Strangely, not long after its publication in 1962, Jackson suffered a nervous breakdown and succumbed to acute agoraphobia (“I have written myself into the house”). She didn’t go outside for six months and took another eighteen months to recover enough to even write. She eventually began a journal, in which she sought to find a new theme for her writing, happier topics. Seventy-five pages into a new novel founded on these intentions, Jackson died in her sleep of heart failure. She was only forty-eight years old.

These were the final words in her journal:

“I am the captain of my fate. Laughter is possible laughter is possible laughter is possible.”

Source: Amazon

Ruth Franklin’s A Rather Haunted Life is published by Liveright.

YouTube Channel: David Barr Kirtley

Featured image via The Slate

h/t The New Yorker