Literature in translation is always a tricky issue: to what extent can a translator impart the essence of the original author without tainting the text too much with the character of their own literary input? And to what extent can readers then accept that translated text as an as-true-as-possible interpretation of the original?

To this end, and others, some authors have skipped the middleman and turned their backs on their mother tongue to write in English.

Dubbed an “exophonic community,” the end goal is fundamentally for the purpose of gaining a wider readership. Additionally, there are reasons both political and personal, let alone stylistic – whether in the sense of the cultural heritage of their mother tongue, or in order to avoid the pitfalls of leaving their texts in the hands of a translator.

Source: Harvard Magazine

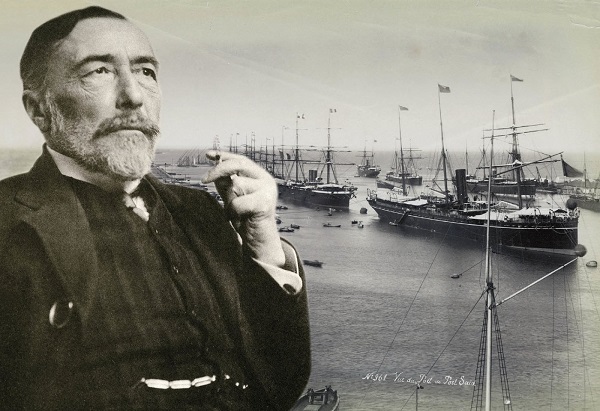

Great authors who have employed such exophony include Joseph Conrad. The Heart of Darkness author was a Polish merchant-marine captain who only gained British nationality in his late twenties. Conrad never lost his Polish accent. Never mind that English was his third language (after French). His reason for writing in English? Its plasticity. And to this end, he was a master. As The Telegraph wrote,

“Conrad’s writing can be hard going – tortuous, choppy, syntactically awkward – but beneath this apparent chaos is a meticulous lexical precision, while his stream-of-consciousness style is one of the finest examples of early literary modernism.”

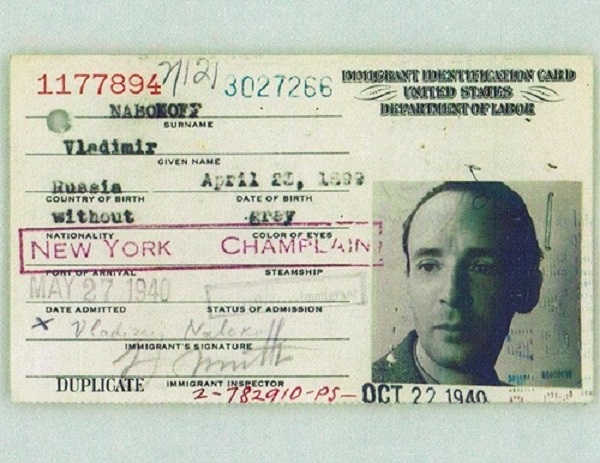

Of course, even more extensive an exophonic author was Vladimir Nabokov. Having fled his native Russia in 1919, the Pale Fire author went to study in Cambridge, lived in Germany, and eventually moved to the United States to lecture in comparative literature. Comparing Nabokov with Conrad (and later such writers), this learned multilingualism becomes an apparent pattern in exophones – but then, such internationality is what leads to textual creation in that most international of languages: English.

Source: Tumblr

Indeed, Nabokov was as good at pinning down the correct word needed as he was in his passion for lepidoptery, his writing never faltering in lexical precision and delight – whatever the language. In fact, The Telegraph describes the 1955 Lolita as “a polyglot’s love letter to language scurrilously dressed up as a pederast’s love letter to a sullen child.”

Source: Tumblr

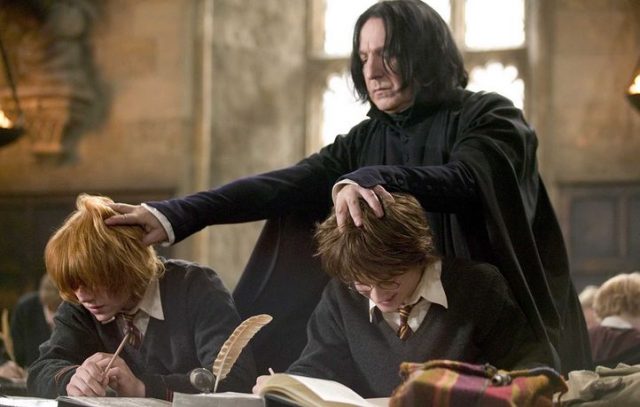

Such exophony doesn’t just exist in foreign-language to English translation, either, but from English to various other tongues. For instance, Irishman Samuel Beckett famously opted to write in French (as did the Czech author Milan Kundera), precisely to escape the stylistic restraints his native tongue put on him. A desire also echoed in Conrad’s purpose. The Telegraph explains,

“For Beckett, English felt too cluttered: psychologically, linguistically, emotionally. Writing in a second language allowed him to pare things back.”

Source: Pinterest

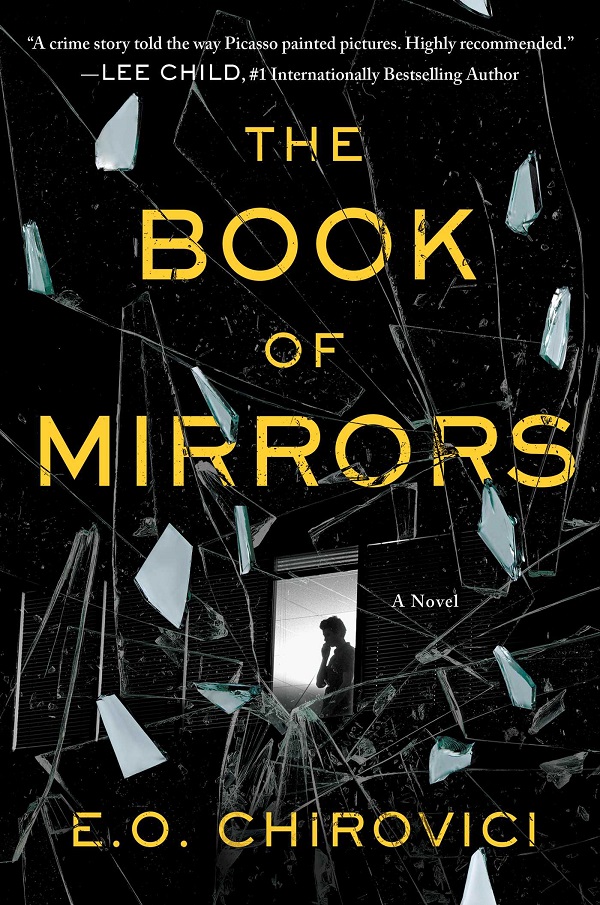

This was not simply a 20th Century literary tactic. Today’s exophonic authors include Eugen Chirovici, a Romanian whose murder-mystery, The Book of Mirrors, was eagerly snapped up for a seven-figure sum by the publishing world last year (its release date is set for February 2017).

Speaking to Toby Lichtig last December, Chirovici discussed the reasoning behind opting to write in English:

“Growing up behind the Iron Curtain, he felt that England and America stood for freedom, and this stoked his passion for the works of the Anglo-American canon […] English is the new lingua franca nowadays.”

Source: Amazon

There is certainly commercial sense in this ongoing tradition of exophony: as The Guardian recently reported, only 7% of fiction books sold in the UK in 2015 were foreign-language translations into English (just 1.5% of books published overall).

When you pause to consider that this section of the market includes authors like Haruki Murakami, ever popular Swedish authors, and the recently unmasked Elena Ferrante, it is at first puzzling. However, those who don’t make the bestseller list are not deemed up to par. Alexandra Bücher of Literature Across Frontiers explains,

“I don’t think we are getting the picture of piles of translated books not selling, because booksellers are really picky about who ends up on the shelves […] The independent booksellers who were happier to get translated books are disappearing.”

Source: The Pool

Therein lies the rub, and the whys and wherefores behind the need for exophones like Turkish-speaking Elif Shafak, Nadeem Aslam (Urdu), Yiyun Li, Ha Jin, and Xiaolu Guo (all Chinese), Gary Shteyngart and Boris Fishman (both Russian), and Bosnian-speaking author Aleksandar Hemon (who published his first Anglophone story only three years after having had to remain in the States due to war breaking out in his home country).

In short, it makes commercial sense. And yet, Anna Webber of United Agents made a general admission:

“[T]he problem is that not many publishers speak foreign languages […] This is why I have to stick to representing a low number of foreign authors – about 10% of all the writers I work with.”

Source: Amazon

From this gloomy statistic (and the fact that most schools don’t promote the reading of foreign-language books, creating in society a foundation of inability to consume foreign literature in its original form), exophony can perhaps be seen as a case of self-perpetuating this “boundary” to Western publishing success.

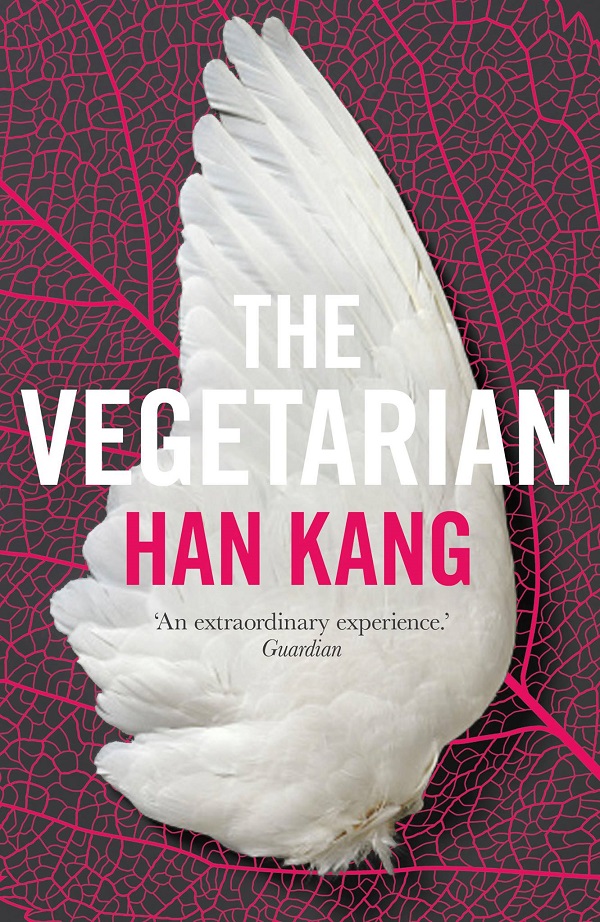

Nevertheless, there exists hope for change in the form of the Man Booker International Prize for literature in translation, which has been going since 2005 (the latest winner being The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith).

Only time will tell. Until then, the maturing tradition of exophony successfully continues apace.

YouTube Channel: Top5Roundup

Featured image via Idlewild Books

h/t The Telegraph